Understanding Brain Drain in European Regions

In European regions, the competition for skilled labor intensifies as global and EU-wide mobility increases. This phenomenon, exacerbated by the free labor movement within the EU, has led to significant shifts in highly educated populations among regions. Small and medium-sized cities are increasingly attractive to young students and graduates due to lower living costs and better quality of life compared to larger urban centers. The term “brain drain” that originated in the mid-20th century is used to describe this phenomenon that has sparked debates on its economic and social implications.

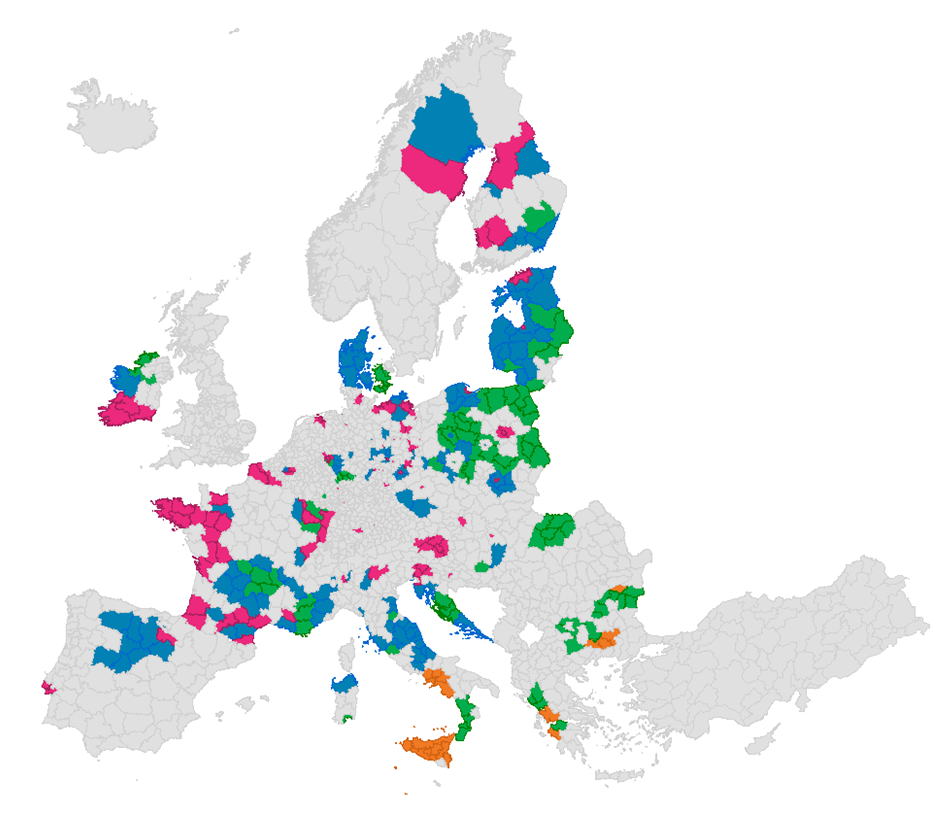

To contribute to its understanding, we mapped European university cities, analyzed graduate migration patterns, and classified regions based on their brain drain dynamics. We give insights into the factors driving skilled migration and explore policy proposals to support regional development and mitigate brain drain across the EU.

We focused on data provided by Eurostat and the European Tertiary Education Register (ETER). Using a two-step approach we estimated Human Capital Production indices based on ETER data and determined Human Capital Stock indices based on Eurostat data. By comparing these two indices for each region, a Brain Drain Ratio is derived. Regions where this ratio exceeds 1 indicate a net outflow of high-skilled individuals relative to their production, identifying them as brain drain regions.

Based on a sound literature review on the factors influencing the migration behaviour of highly skilled individuals, we then added a set of multi-dimensional socio-economic indicators to rank and cluster the concerned regions into groups. The result is a typology with four types of regions, each facing unique challenges.

The Basic

In this category, we find smaller cities in proximity of rural areas that cover local and regional demand for tertiary education. These cities are experiencing problems related to socioeconomic (unemployment, lack of technological progress, poverty, social exclusion), demographic (population loss, aging) and physical factors (poor infrastructure and housing). Most of these regions have an agricultural tradition with a low industry mix and low accessibility. Their economic development is below average and while offering education opportunities in proximity for households with no other access to education, they do not provide any opportunities for their graduates than to leave. Universities in these regions do not just struggle to retain graduates but also to attract students which limits the universities contribution to the local economy as well.

The Emerging

These regions comprise cities, mostly peripheric, with low population density and tradition in agriculture and/or specific areas of manufacturing (clothing, leather, furniture etc.). The relocation and polarization of economic activities caused by the globalization in the last decades has led in these cities to a failure to carry out the shift from traditional manufacturing to innovation-driven industries and modern business-oriented services. This affected the economic power of urban areas and deteriorated the fiscal base of cities, leading to financial bottlenecks impeding the maintenance of local infrastructure levels and deteriorating quality of life. As a result, the challenges related to vacant and underutilized housing, uncompetitive, old local businesses, as well as a poor infrastructure have rapidly emerged. Universities were matched to the industries located in these regions and are residuals of a past industrial structure. Sometimes, universities are purposely located in these regions to contribute to urban growth.

The Advanced

In contrast to the first two categories, a lot of bigger cities or smaller cities in metropolitan areas that do face structural problems and low industrial diversity, can be found here. These cities benefit to a certain extent from agglomeration effects or positive spillover effects from bigger cities in their proximity. However, due to low flexibility and risk-aversity these cities do lack innovative performance and economic growth. Their problems are induced by multidimensional aspects such as changes in socio-spatial structures, changes in labor market flexibility, financial deepening, the increase of the skill premium caused by technological progress as well as deindustrialization. Consequently, some of these cities appear to be suffering from the lock-in effects caused by the path dependence, which is determined by traditional socioeconomic structure, less-speedy industrial evolution, and inefficient production practices. Universities are an organic part of the urban infrastructure and very often one of the most important contributors to local development. Also, their reputation allows them to attract national and international students.

The Frontrunners

These cities and regions experience a certain level of economic dynamism, sectoral heterogeneity, involvement in global production processes, R&D investment, and human capital. However, the cities sometimes lack certain types of important social capital such as accessibility shortcomings of firms’ R&D cooperation with local research institutes and universities, missing knowledge transfers and personal exchange between firms. In some cases, these cities are so called consumer cities that focus on culture, art, tourism, and research but in many cases low entrepreneurial success. Universities are well known and attract many national and international students without having a matching labor market. Graduates are being pulled by regions with better opportunities. Amongst these cities are also capital cities in eastern Europe that despite economic growth compete with regions abroad that are more attractive to graduates.

What type of region are you?

Fill in this brief questionnaire to find out what type of region you are.